July 31, 2017

No matter where you work — from a commercial kitchen to a busy construction site — it’s critical to identify all the ways you can get burned.

Across industry, some of the most dangerous burn hazards are unforeseen. The more expected and obvious risks — stoves in a commercial kitchen, for example, or torches used by welders — are rarely the source of the most serious burns. Instead, it’s the things you might overlook that can wreak the most havoc.

Yet what you don’t know about burns can — and will — hurt you.

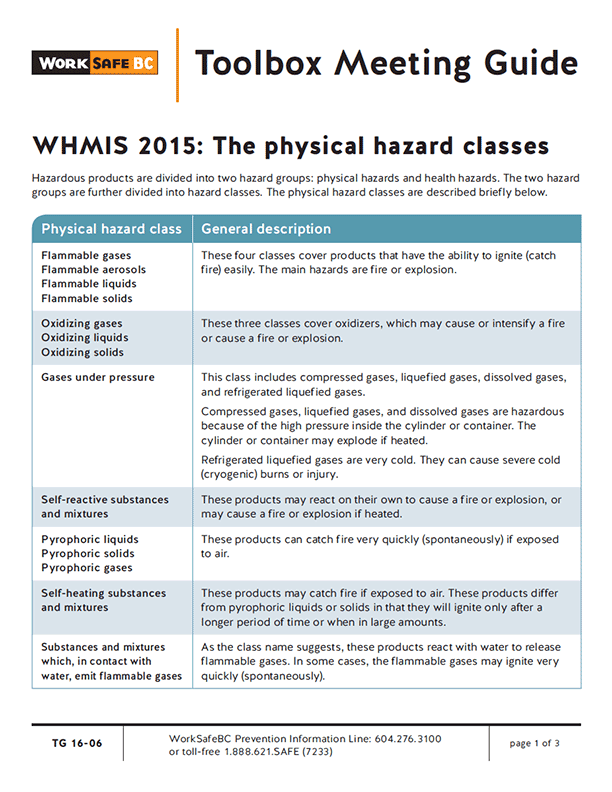

Chemical burns, for instance, are a common source of “surprise burns.” What these burns lack in terms of pain, they make up for in severity, says WorkSafeBC senior regional officer Candace Mayes.

“Some acids can be sneaky,” Mayes explains. “They interact with your nerves, and you don’t even know you’re being burned.” As Mayes points out, contact with even a small amount of hydrofluoric acid, for instance, can be lethal.

Mayes says clear communication in the workplace can go a long way toward reducing the risk of being burned. A welder who marks a just-welded pipe with chalk to say “hot,” a cook who says “coming through with boiling water!,” or an employee who properly labels a chemical product can prevent a nasty burn. A worker who notes the contents on the outside of a fuel tank or drum can even save a life.

“It takes very little fuel to cause an explosion,” says WorkSafeBC occupational safety officer Doug Fielding. “If a welder works on a container without knowing what’s inside, a spark or heat can cause a deadly incident.”

Even with careful hazard identification, though, unexpected risks remain. Concrete, for example, is a real-but-insidious source of chemical burns — the second-leading cause after cleaning agents. “It’s wet and it has a high pH,” says WorkSafeBC occupational hygiene officer Alanna Nadeau. “If a worker gets it down their boot, it feels cool and squishy, and nothing at all like a skin-burning chemical.” The all-too-common response? You’ll continue to pour; completely unaware you’re being dealt a second-degree burn.

Nadeau remembers one diligent worker who was intent on completing a perfect pour. “He got a big blotch of concrete in his eye and just rubbed it off. He was pouring a pool so he felt it was critical not to stop. He could have lost his eye. But because it was cool and wet, he didn’t think it was going to cause any damage.”

Welding, not surprisingly, comes with its own burn risks. It’s not necessarily the equipment, though, that’s the culprit, but the flakes of molten steel that can sneak in and stick to delicate tissue. Between 2007 and 2011, in fact, 153 BC workers were burned by molten metal, versus just 13 by the torches themselves.

“Your eye is like a magnet for the flakes,” Fielding says. “And if anything gets in your ear canal, you can’t cool it.” The same applies to untied or open-top boots; if molten droplets get in, you can’t get your boot off in time to prevent a serious burn.

A snowy mountaintop may not seem the most likely place to suffer a burn, but ski hill employees are susceptible to another all-too-common type: frostbite. Also known as “cold burn,” frostbite is as stealthy as they come; often painless, it can cause blistering, edema — even leading to gangrene and amputation.

Burns are a familiar occurrence in commercial kitchens, too, of course, but not necessarily from the most obvious sources. “My first job was working as a dishwasher in a local family restaurant,” says Brian Riley, now health and safety manager for Aramark, a global food service provider. “Steam tables can be a common source of burns; even just washing dishes with very hot water.” In fact, while big commercial stoves may appear to be the most likely cause of big burns, it’s more often the seemingly less risky tasks that result in injuries.

WorkSafeBC occupational safety officer Laddie MacKinnon sees almost seven-and-a-half times more burns from hot water and oil than from ranges and ovens. Burn-causing splatters can come from carrying simmering soup across a busy kitchen, pouring hot liquids out of industrial-sized pots, or putting wet food into a deep fryer. And because oil can hold its heat for hours, deep fryers can be dangerous even to those not involved in food preparation. Late-night cleaners can step into uncovered oil when climbing up to clean vents — with devastating results.

Using the wrong tool is at the root of many incidents, Riley says. Although it’s common for a cook to grab a dishtowel to handle a hot pan, a proper oven mitt is essential. “A towel doesn’t provide the same coverage,” he says, “and it often holds moisture, which turns to steam and burns worse than the hot pan itself would.”

In kitchens and many other workplaces, acids and bases in cleaners and degreasers pose another hazard: chemical burns. When splashed into eyes, certain products can cause blindness. Used as mist, they can burn lungs and respiratory tracts, and even lead to death.

“The risk that comes from dealing with a chemical depends on two things,” Mayes says, “its concentration and the duration of contact.” She suggests reducing the risk and severity of chemical burns by using non-corrosive substitutes, or — if none are available — by using the most diluted form of the product for the shortest duration possible. But, she warns against buying concentrated versions and diluting them yourself, a money-saving, but splash-inducing, practice.

Mayes also stresses the importance of disposing of unused chemicals, which can eat through their containers. And if contact does occur, she says, it’s important to wash more thoroughly than you might think. Some chemicals can continue to burn long after any discomfort has subsided.

Most importantly, she says, be alert to the unexpected in every work situation. And encourage others to remain alert as well. “Some hazards — on the construction site, on the ski hill, and in the kitchen — are much trickier to identify and prepare for than others. But take steps to be prepared, anyway.”

Be Burn-Savvy

- Wear protective gear that’s appropriate to your task and environment. Use non-slip, closed-toe footwear when in a kitchen, eye and ear protection, and non-flammable clothing when welding, chemical-resistant gloves when dealing with corrosives, and waterproof layers when on the ski hill.

- Practice good housekeeping. Keep kitchen floors clear and dry: “Slips and falls are one thing; slips and falls onto a hot item are another,” says Aramark health and safety manager Brian Riley. Cover hot oil when not in use. Never store chemicals overhead.

- Communicate clearly. In the kitchen, let others know that you are carrying hot liquids or foods. When using chemicals, mark all containers clearly. On construction sites, write “hot” on recently welded pipes.

- Know the risks. Pay attention during training, read the labels on chemicals, and study all materials safety data sheets (MSDS). If you are going to weld, grind, or cut any tank, work in accordance with approved standards, such as required combustible and toxic gas testing.

- Be prepared if an incident happens. Familiarize yourself with emergency procedures, including how to use the emergency wash station.

By Susan Kerschbaumer. Reprinted with the permission of WorkSafe Magazine, WorkSafeBC.

This article may not be republished without the express permission of the copyright owner identified in the article.

go2HR is BC’s tourism & hospitality, human resources and health & safety association driving strong workforces and safe workplaces that deliver world class tourism and hospitality experiences in BC. Follow us on LinkedIn or reach out to our team.